Natural fibre Craft

Handcrafted items from sustainable materials

Natural fibre Craft

Crafting with fibers isn`t just about skill; it`s a blend of nature know-how and well-kept expertise. The skilled makers in the communities infuse their creations with a uniqueness that sets them apart. Over time, they`ve not only preserved their cultural heritage but also given it a modern twist.

Each fibre brings its flair to the table – be it strength, smoothness, density, color, or fragility – traits that the local communities know like the back of their hand. The indigenous communities have mastered the art of processing these fibers to get just the right materials, showcasing their cultural traditions in every crafted piece. It's like they`ve cracked the code to nature`s crafting manual!

Bamboo

Basket weaving has been practiced as an ancient art form in India, with rural communities crafting unique shapes and patterns for baskets that reflect their local traditions, necessities, and techniques. In the past, skilled artisans created baskets and winnows, which are tray-like bamboo baskets commonly used in Bengal for both daily activities and rituals. These craftsmen also fashioned various items such as hand-held fans, sieves, and more, adorning them with auspicious symbols for use in ceremonies like weddings.

Process

- Cutting and Soaking

- Drying and Shaping

- Colouring and Dying

- Weaving

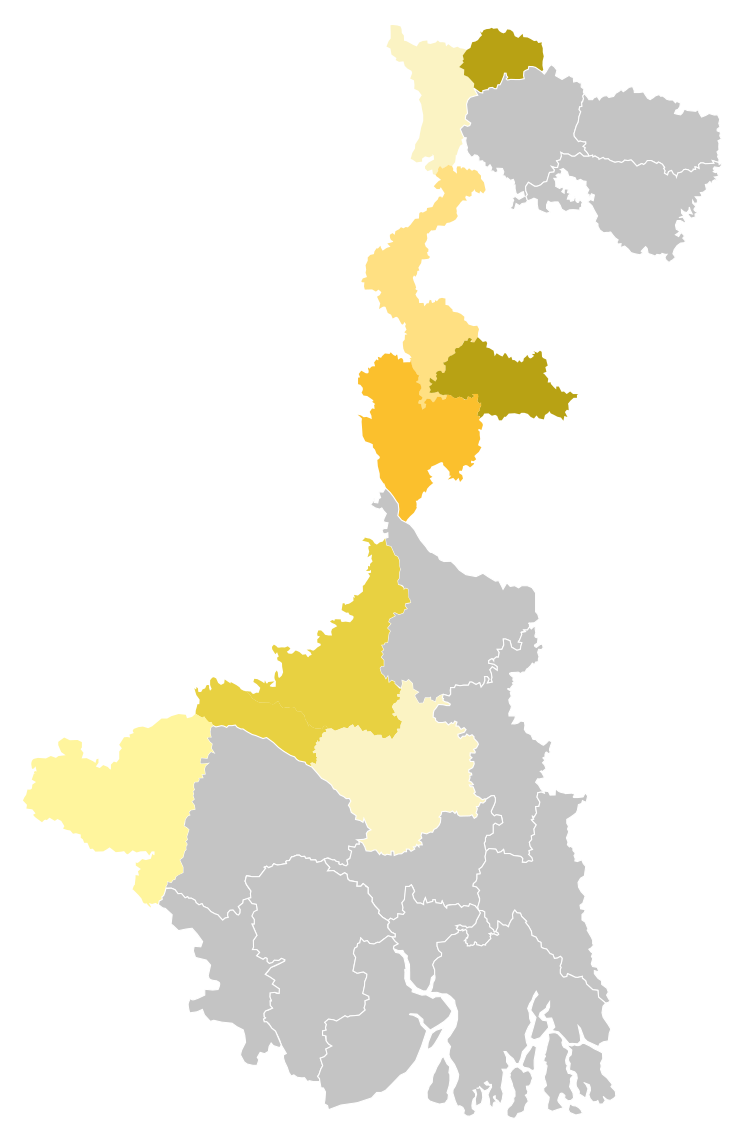

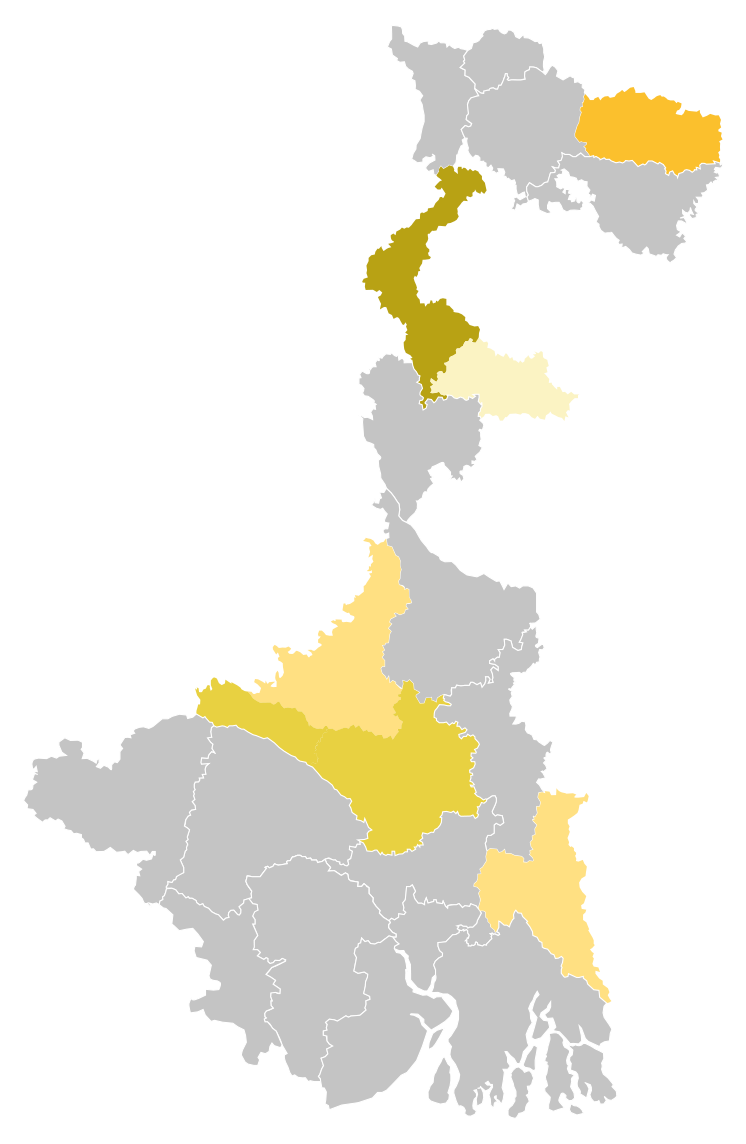

Bamboo Hubs

Dhokra

Dhokra, a rural handloom tradition, involves weaving jute mats in the Uttar and Dakshin Dinajpur districts. The weaving process takes place on back-strap looms within households. Locally sourced jute, known as the `Golden Fibre,` serves as the primary material for crafting Dhokra mats and various other products. This traditional art form plays a crucial role in providing livelihoods for numerous women in the region.

The practice of Dhokra weaving has been officially recognized since RCCH I (2016 onwards). The Uttar Dinajpur district is home to 1468 Dhokra weavers, while Dakshin Dinajpur boasts a community of 2634 weavers actively engaged in this craft.

Process

Cutting and Soaking

Drying and Shaping

Colouring and Dying

Weaving

Dhokra Hubs

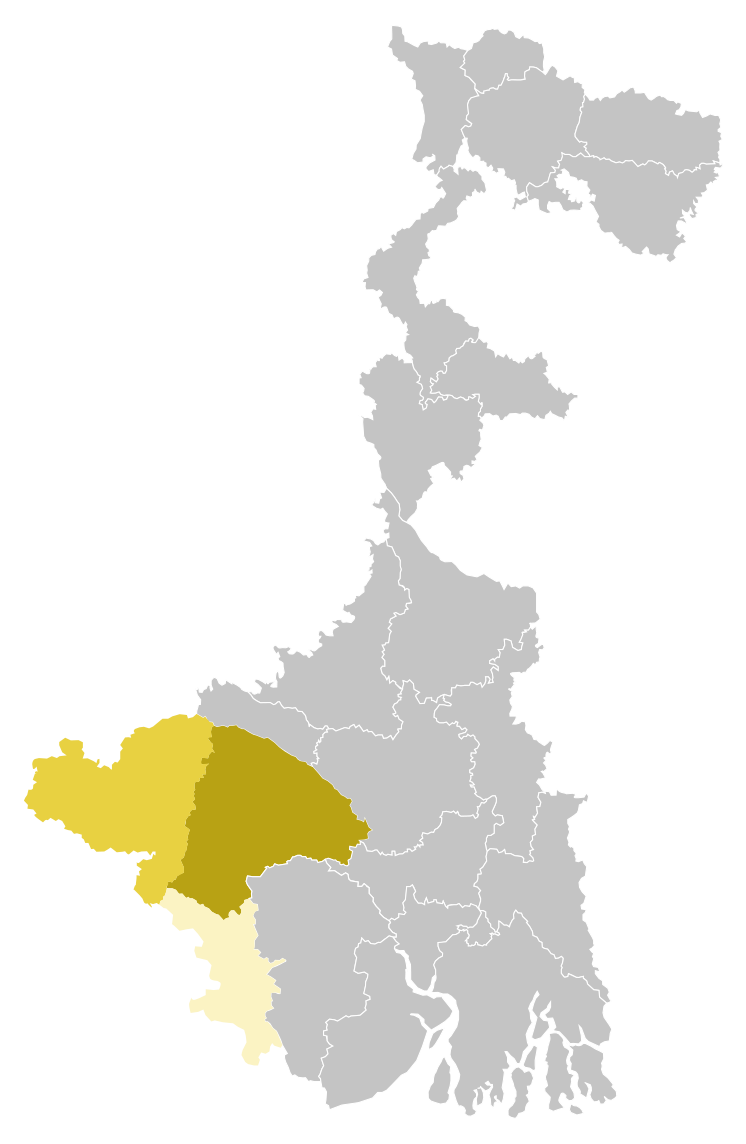

Sabai

The local name for the fiber or grass in the region is Babui Ghash, thriving abundantly in the forest fringe areas of Purulia, Bankura, and Jhargram. Women gather the grass, meticulously washing and drying it before twisting it into bundles to create ropes. The traditional livelihood centers around crafting ropes, which are then sold in the local market. Over time, Sabai artists, through skill enhancement, have expanded their repertoire to produce diverse products, elevating their market presence at both the state and national levels. Currently, there are 4730 Sabai artists engaged in crafting these products.

Process

Harvesting

Forming ropes and Smoothening

Bundling

Thali

Weaving

Sabai Hubs

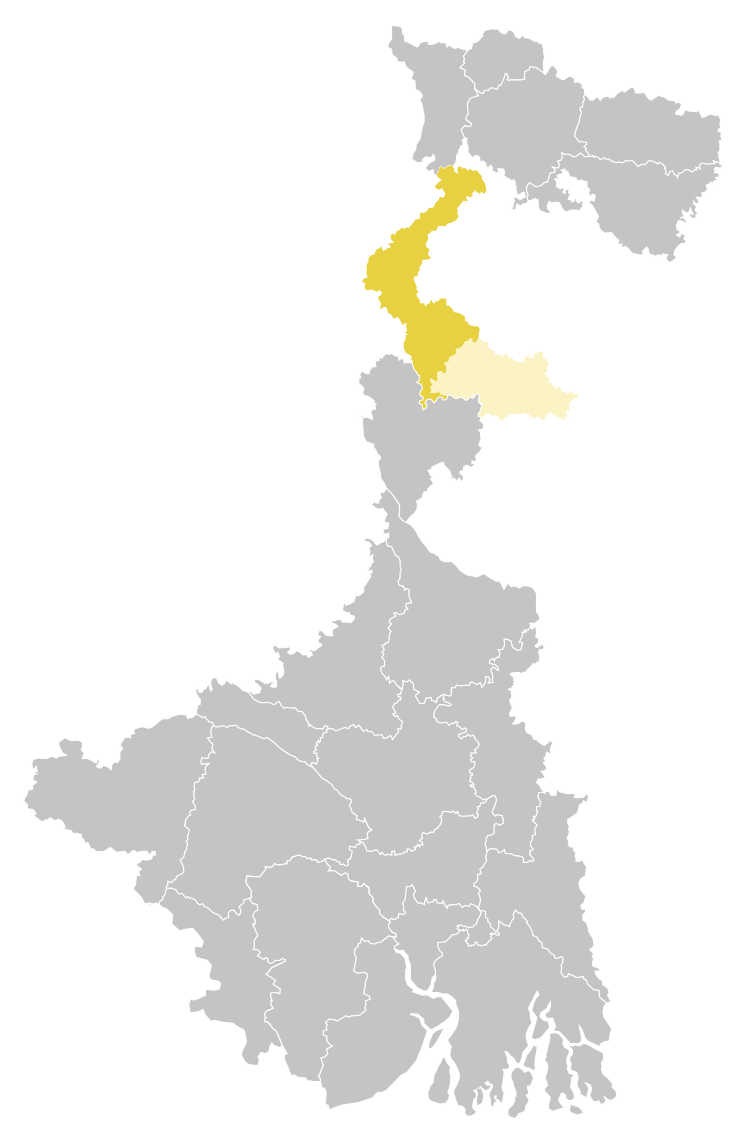

Sitalpati

Sitalpati is crafted using cane slips extracted from the cane bust, with the quality of the Pati relying on the distinct layers of the cane. This type of cane thrives abundantly in the Coochbehar district of West Bengal. The process involves cutting fine cane slips, which are skillfully woven to create household mats known as Sitalpati, translating to cool mats. The industry is primarily family-oriented, with men dedicated to growing and extracting fiber, while women are primarily involved in the weaving process.

Process

Preparing the cane strips

Colouring

Dyeing

Weaving

Sitalpati Hubs

Shola

In the early 20th century, Shola craftsmen, originally from Chittagong (now in Bangladesh), migrated to Bankapasi in the Bardhaman district. Here, they began crafting ornaments and decorative items from Shola pith, finding a market among the clay idol-makers in Kolkata's Kumartuli. This marked the start of Shola craft gaining popularity, eventually leading to its widespread use, including the creation of the popular Daker Saaj for Hindu deities' idols, across Bengal and beyond. Shola pith, a delicate ivory-colored reed, thrives in the moist and marshy lands of Bengal, Assam, Odisha, Andhra Pradesh, and Tamil Nadu.

Process

- Shola Growth

- Harvesting process

- Material Collection

- Crafting Decoratives

Shola Hubs

Madur

In Bengal, the term "Madur" serves as a generic term for floor mats, which hold a significant place in the lifestyle of the region. This weaving tradition is not just a craft but a source of pride for Medinipur. Typically, women from households actively engage in the intricate process of weaving these beautiful Madur mats. These mats find their way to local markets for everyday use and are also transported to neighboring states for ritualistic purposes. Responding to evolving market demands, weavers have expanded their craft to create both decorative and utilitarian items.

Process

- Preparing the cane strips

- Colouring

- Dyeing

- Weaving

Madur Hubs