Folk Painting

Colors that narrate Bengal’s folk stories

Folk Painting

Painting, as the oldest medium of human expression, finds diverse forms in West Bengal. Folk paintings, narrating stories of the painter communities' lifestyles and beliefs, have captivated art lovers for ages. Alpona, or painted motifs and symbols on doorways and walls, is a common tradition in Bengali households. Thangka painting in hilly regions reflects native mountain culture. Folk painting traditions intertwine visual storytelling to sustain local folklores and mythologies, drawing inspiration from nature.

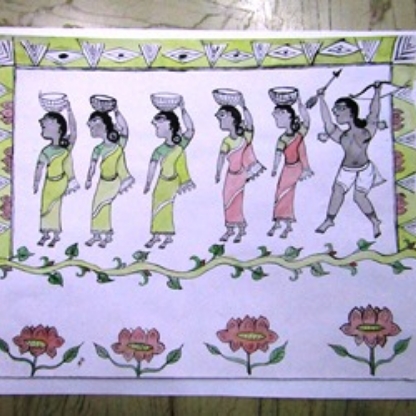

Bengal Patachitra

Patachitra, an ancient folk-art originating from Bengal, is a form of traditional scroll painting on cloth. The artists, referred to as 'patuas,' skillfully depict a wide range of subjects, including mythological tales, tribal life, rituals, local legends of Hindu deities, contemporary stories, historical events, and more. Using natural colors derived from trees, leaves, flowers, and clay, these painters create vibrant and captivating artworks.

Accompanying the scroll paintings are songs called 'pater gaan,' which the patuas sing while unveiling the scrolls.

Process

Draw outlines on cow dung-washed paper,

fill with color.

Strengthening

Paste recycled fabric on the reverse side.

Natural drying.

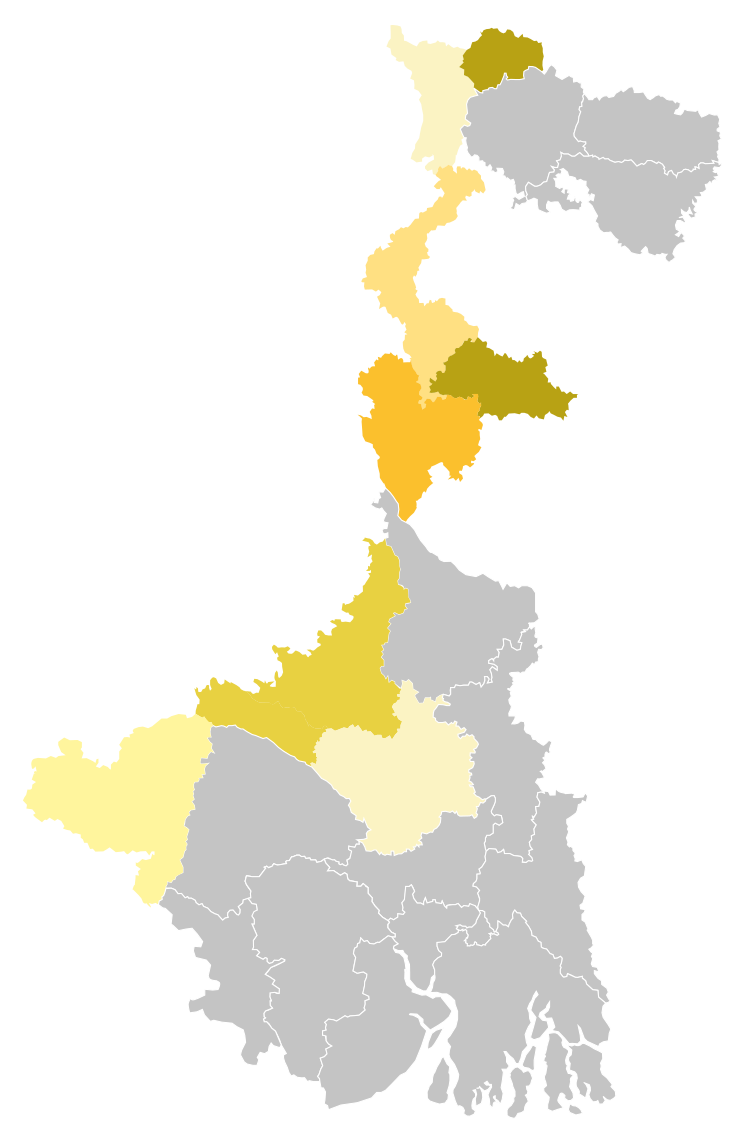

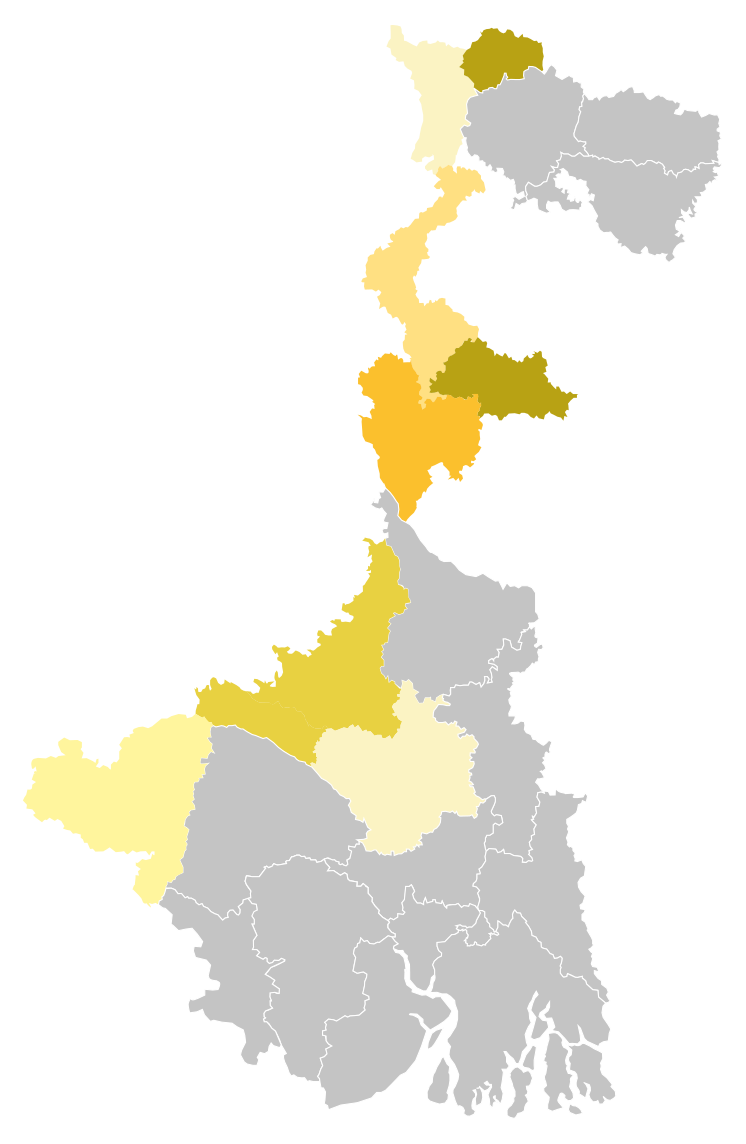

Bengal Patachitra Hubs

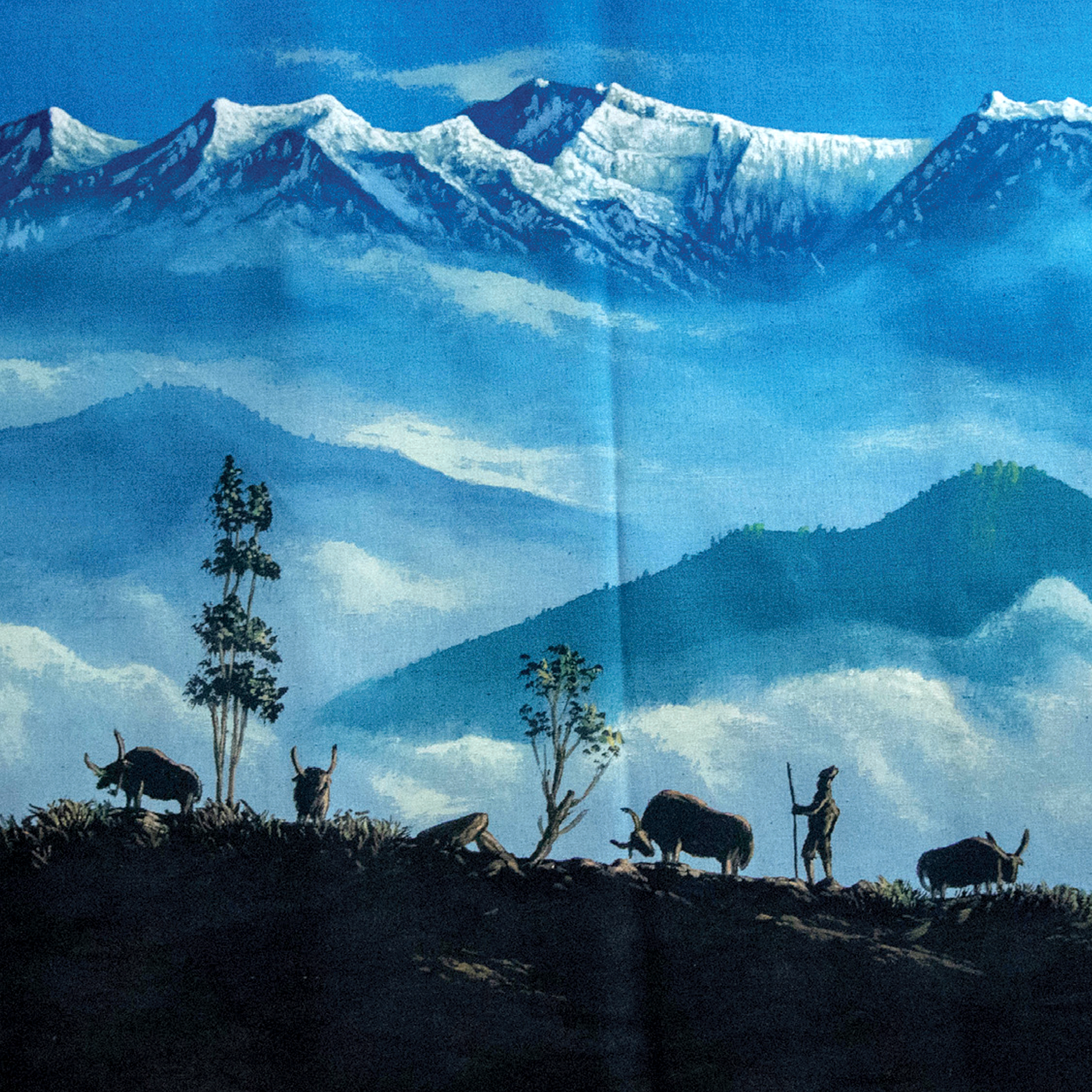

Hill Painting

Hill painting in Bengal is an artistic tradition flourishing in the scenic landscapes of Darjeeling and Kalimpong. Local artists, skilled in the craft, have been adorning cotton fabrics with captivating scenes from nature for years, creating a unique and popular form of art that serves as a cherished souvenir for tourists exploring the hills of North Bengal.

Process

Fabric Selection

Base Colors

Direct Brushwork

Evolution of Medium

Color Application

Fabric Enhancement

Drying Process

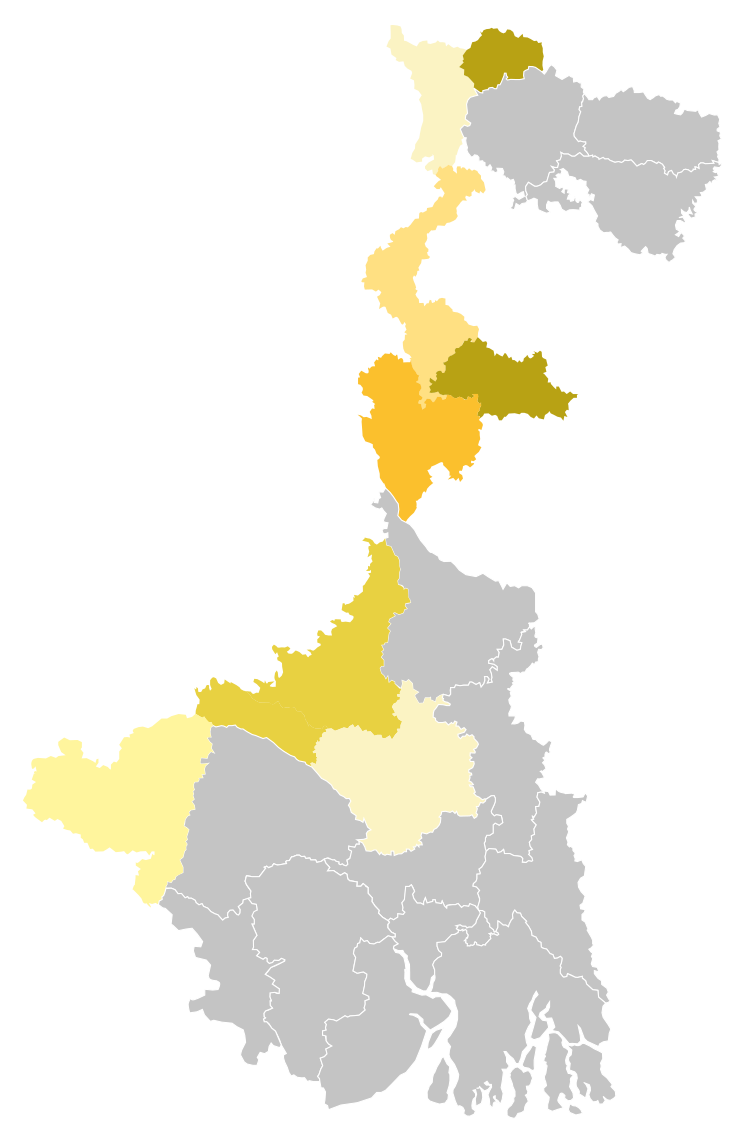

Hill Painting Hubs

Folk instrument

Folk musical instruments are mostly hand-crafted in India. West Bengal has a good number of skilled artists who craft instruments meticulously. The tradition is mainly popular in districts like Nadia, Purulia and Bankura. Considering music and dance is an integral part of the rural tradition, the crafting of the instruments play a pertinent role. String instruments include Gopiyantra, Dotara-a basic two-stringed instrument, Sarinda- a bowed lute, Banam- a wooden instrument, percussion instruments like Dhaak and Dhol.

Process

Dhamsa : The instrument structure is like a pan. Its structure is made of iron sheet and the cover is made of buffalo skin. The instrument is played with the support of wooden stick. Initially the hollow structure is made of iron sheet and then the cover is being put on the same. The dome shell is fitted with a leather ring to provide a base on the ground, made of leather lace. The ribs are tightened by placing them in the holes made on the outer edges of the overlaid leather. Tightening increases the tone and loosening make the tone slower and thicker. Silt is applied in the middle of the overlaid leather. The same technique is used in the medium and small sized nagaras.

Dhol : The Dhol is usually made from jackfruit and mango wood. For this, a wooden shell of about three and half feet diameter is opened. The middle part of the wood is slightly embossed. Both open ends are covered with goat leather. To tighten the skin of these two ends, they are tied around the forehead. Tightening and loosening in the leather are done up and down by the threaded metal ring in these fibers.

Madol : It is made by piercing of leather at either side of the open ends of a circular shell, about 3 to 3.5 ft long, of wood. Goat leather is used for mounting. Thin leather is tightly wrapped around it. The fabric is attached at both ends by making small holes in the upper end of its rounding and attaching it to a thin strip of leather. By tightening, these thin strips, the tension on both sides gets tight and the tone increases when beaten and the tone becomes thicker when loosened. The diameter of the left handed end is larger than the right handed end. The leather on the right hand end is slightly thick and rough.

Dotara : Dotara is usually made with items like, wood, steel, leather (typically stretched goat skin), strings (cotton/ nylon/ steel/ raw silk/bronze), tail piece (metal in modern design), wooden main bridge, knobs/ears/pegs (made of wood) and polishing materials. The wood is chopped into shape at the primary stage. Then the lower part is hollowed neatly because the sweetness of the sound depends mostly upon the shaving off of wood in the lower portion of the instrument. Then a peacock or common bird design is made on the upper extension. Goat skin and a metal plate are placed over the lower and middle portion, respectively. Again the thickness of the skin should be minimum for better tonal quality. Polishing and attaching the strings from the lower tail piece to the ears on top is the last thing to be done.

Folk instrument Hubs

Purulia Patachitra

The Patachitra form practised in Purulia is strikingly different from the one in Medinipur. Purulia’s Patachitra stands out for its simple style and compositions, minimal background decoration, and use of natural colours made from stones and leaves. The Patachitra of Purulia is essentially a ritualistic practice associated with the events in the daily lives of people. Unlike its counterpart in Medinipur, Purulia Patachitra is relatively lesser known to the outside world. And so is the artists’ use of organic dyes. Created with simple, bold strokes, there is minimal use of colour and decoration, and rarely does one see more than two-three colors in the frames, but they stand out for their sheer aesthetic brilliance. As the base material they use paper easily available in the market. Especially, fullscape. The method to make the base strong and long lasting is not known. They have little idea of preservation. At the beginning of making pat, about 8’’ – 1’ part of the same is covered with plastic, which is easily available. It is done primary to protect the rest of the paper from water. Two handles on two sides are made with bamboo strips, help the artists to wind up the pat. It also becomes easier for the artists to unfurl the pat with the two handles.

The Pater Gaan or the songs accompanying the scroll paintings showcase the culture of tribes like Santhals alongside the mainstream fare. There are many songs in Alchiki, reflecting an interchange of languages, and Santhal Pats coexist in harmony with the likes of Madanmohan Leela, Krishna Leela and Raas Leela. The spectrum of natural colours and their sources is amazing. Saffron is created from Geru Pathar stone, yellow ochre from Holud Pathar stone, white from Khorimati clay, black from a type of soot called Bhushokali. Orange comes from Kamala Pathar stone, green from Simpata leaves, purple from Pui Metuli leaves, pink from banyan buds or Boter Kuri, red from Phanimansha flowers, blue from Nil, and yellow from Palash flowers!

A total of 71 artists from Majramura village located in Purulia district are covered under the RCCH project.

Process

Materials and tools used to create Patachitra include paint brush, paper and colours. The colours are extracted from stones. The colour extract and glue mix is dried in the sun before use. Chitrakars follow a common process while painting Patas. As the first step they draw outlines of the paintings on paper that is washed with cow dung before use to protect it from pests. The line drawings are then filled with colour. Finally the paintings are dried naturally. The songs which are locally known as Pater Gaan are written and performed with the traditional scroll-Pata by the artists.

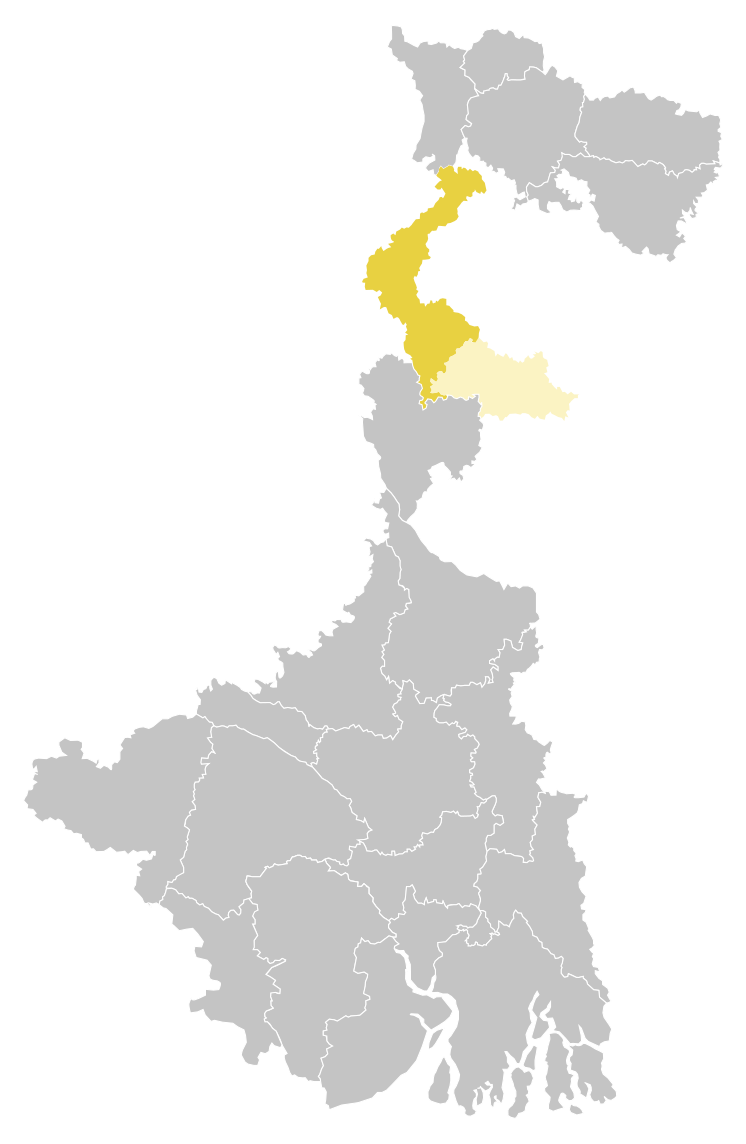

Purulia Patachitra Hubs